Le Corbusier’s work is closely associated with the Neues Bauen movement – a new building style that emerging in Germany after 1900 – and with the development of the Modern Movement after the Second World War. The first third of the 20th century in particular witnessed powerful and fruitful interaction between Le Corbusier and modern trends in Germany, despite this interaction being subject to antagonisms and radical breaks.

Le Corbusier’s stays in Germany had already proved a rich source of inspiration before the First World War. In turn, his written and built work had been known in Germany since the 1920s, and was the subject of lively discussions, characterized by both admiration and rejection, traces of which are still with us today. These have recently been documented by important exhibitions in Weil am Rhein (2007) and Berlin (2009) covering all his architectural and artistic work and visited by large numbers of people.

Long before he was known as Le Corbusier, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had taken an intense interest in the Modern Movement emerging in Germany and in Austria. During an extended stay in Germany from April 1910 to April 1911, he visited various cities to inquire into the Deutscher Werkbund, founded in 1907, a movement which had rapidly become the driving force in German cultural renewal. Jeanneret met representatives of the Deutscher Werkbund, including Peter Behrens, Heinrich Tessenow and Karl Ernst Osthaus. In Berlin he worked for several months in the studio of Peter Behrens, who not long before had also played host to Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

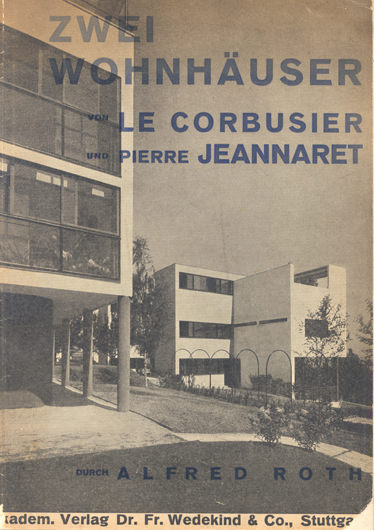

The importance of Le Corbusier for the Modern Movement in Germany can be seen above all in his participation in its two biggest architectural exhibitions: those of the Werkbund in Stuttgart in 1927 and the Interbau in Berlin in 1957.

It was a very self-assured Modern Movement that was on view in 1927 at the Weissenhof in Stuttgart. It was led by German architects most of whom were members of the ‘Ring’, a group of Neues Bauen architects founded by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.The Deutscher Werkbund, open to foreign influences, also invited the most important representatives of the Modern Movement in Europe, with whom it was in close contact.

At this time, Le Corbusier was an independent figure in architecture and an influential theoretician in Modern Movement circles in Germany. In 1923, he participated in the large Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar. In 1926, Vers une architecture, his first collection of critical essays, was translated and published in Stuttgart under the title Kommende Baukunst, arousing considerable interest within the Movement. As the exhibition’s artistic director, Mies van der Rohe resisted all attempts to exclude Le Corbusier from the 1927 Werkbund Exhibition in Stuttgart, considering that this outstanding event in modern architecture could not forgo the presence of an ‘esprit français’ amidst the new trends in Germany. The atmosphere of renewal in Stuttgart created a favourable background for the creation of the CIAM congresses in La Sarraz in 1928. Their second policy congress was held in Frankfurt in 1929.

With the rise of National Socialism, modern experiments were subjected to increasing political repression. Already in 1925, nationalist attacks forced the Bauhaus to leave Weimar and move to Dessau. In 1929, the Great Depression resulted in almost total paralysis of the building industry. Although the new architecture, known since 1932 as the ‘international style’, was predominantly the work of German architects, it almost disappeared in Germany itself, being at best relegated to specific markets in the war economy until 1945.

In fact, the situation in 1957 was totally different from that of 1927. 1957, the year of the Interbau exhibition in West Berlin, signalled West Germany’s attempt to reconnect with the international architectural scene through a new vision, resolutely opposed to the classically inspired reconstruction style initially implemented in East Berlin. In the context of this international exhibition, the Hansaviertel, a middle-class area in West Berlin, originally of a block perimeter development type (“Blockrandbebauung”) but destroyed during the war, was entirely rebuilt on modern architectural principles. Le Corbusier was of course invited to participate in the exhibition. This gave him the opportunity to build in Berlin the only Unité d’Habitation existing outside France. A few steps away from the Stadium that housed the 1936 Olympic Games, the site constitutes a resolutely Modernist response to the brash monumentalism of National Socialist architecture.

The reconstruction of Berlin and the development of architecture in all West German cities after the war are a clear expression of the ideas put forward in the Charter of Athens. This Charter however, drawn up by Le Corbusier in occupied France in 1943, ten years after the 4th CIAM Congress, was translated and published in Germany for the first time in 1962, at a time when many of the decisions relating to reconstruction had long since been taken and when they were already being subjected to criticism. It was therefore not so much the Charter itself which was implemented in post-war Germany, as the programme contained within it, a programme which had influenced urban planning designs since the 1920s and the CIAM Congresses held before the Second World War.

In the French occupation zone in particular, the first plans for the rebuilding of Saarbrücken, Saarlouis and Mainz constituted a faithful transposition of the theories of the ‘functional city’ formulated in the Athens Charter. In Mainz, a reconstruction plan in keeping with Le Corbusier’s plan for the reconstruction of Saint-Dié was drawn up by Marcel Lods at the request of the French occupying force. The Germans preferred a traditionalist plan by Paul Schmitthenner, who was one of Le Corbusier’s detractors when the Weissenhof housing estate was being designed in 1927.

The concept of a ‘grande unité d’habitation’ as set out by Le Corbusier in La Ville Radieuse and implemented in the Unité d’habitation has become the reference in West Germany

– and, in a different context, also in East Germany– as a determining characteristic of modern urban planning. The social aspects of Le Corbusier’s concept of a ‘vertical city’ were however not adopted. This is why the post war construction of mass housing rapidly acquired connotations of anonymity and inhospitality, reagarded as being specific to modernity.

Today the reception of Le Corbusier’s work in Germany and in Europe tends more and more to stress the pivotal idea of a ‘synthesis of the arts’, appearing in in the correlation between numerous disciplines including architecture, urban planning, painting and design. The global, universal nature of Le Corbusier’s work and his artistic approach, which are modern both in expression and in the media used, has found recognition.

[1] “Le Corbusier – The Art of Archi- tecture”, 29.9.2007 – 10.2.2008, Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein; Le Corbusier – “Kunst und Architektur”, 9.7. – 5.10.2009, Berlin, Catalogue Mateo Kries, Stanislaus von Moos, Arthur Rüegg, parmi d’autres, Berlin 2007.

[2] Cf. Harald Bodenschatz: “Charta von Athen: Fragen an eine Le- gende“. In: Die Alte Stadt 2/2004

[3] Cf. Werner Durth, Paul Sigel, Baukultur, Berlin 2009