Despite the very limited number of works built on Belgian soil (only one has survived), the influence of L’Œuvre Architecturale de Le Corbusier on 20th century Belgian architecture is undeniable.

This influence was particularly felt through his written contributions and publications, beginning with the review L’Esprit Nouveau in 1920.The earliest subscribers to this journal included the Belgian painters René Magritte and René Guiette. As well as Le Corbusier and Ozenfant, the co-founders of L’Esprit Nouveau included the Belgian poet Paul Dermée, who had settled in Paris and was responsible for the journal’s title. Dermée’s participation, however, was brief and he left the magazine in late 1920 following disagreements.

Vers une architecture, published in 1923, did not go unnoticed in the avant-garde press and indeed reached its target audience. Le Corbusier’s publications were the only ones by an architect to be advertised in Belgian journals. Le Corbusier’s influence is also apparent in the many lectures he was invited to give in Brussels and Antwerp between 1926 and 1933. He was even asked to give interviews on Belgian radio as early as the 1920s.

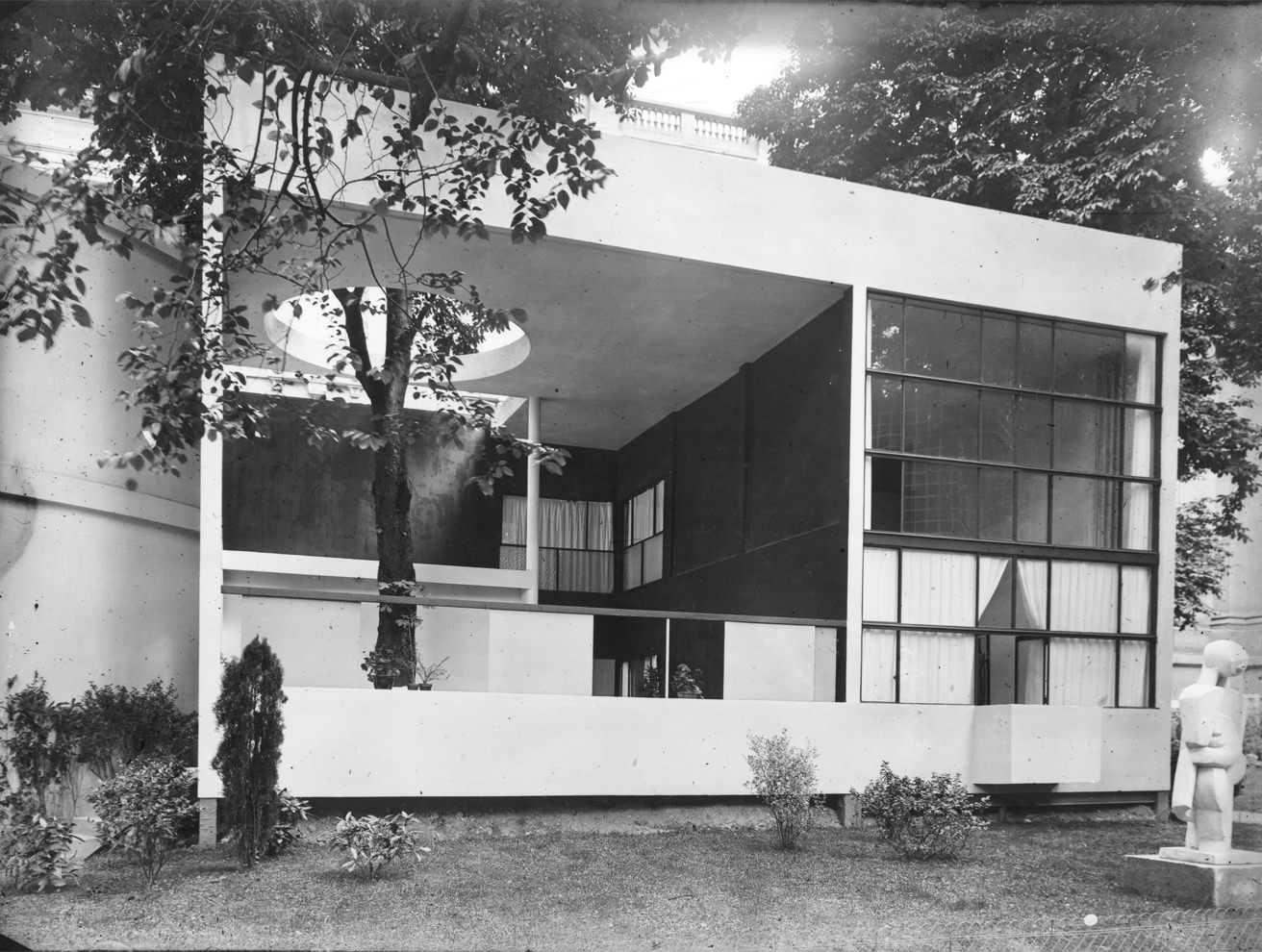

At the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, it was particularly the Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau that impressed the Belgian Modernist artists and architects who had come to Paris.They included Gaston Eysselinck and Leon Stynen, as well as René Guiette. Soon afterwards Guiette commissioned the young Le Corbusier to build him a studio-residence in a new district in Antwerp. At that time, Guiette entertained the illusion that his modern home would help to make of this new district a true manifesto of modern architecture. This was not to be the case and, following the destruction of the Pavillon Philips in 1958, Maison Guiette has remained the only surviving building by Le Corbusier in Belgium. With the exception of his homeland, Switzerland, it was also the first of Le Corbusier’s works to be built outside France.

Maison Guiette belongs to the series of “purist” dwellings to which in the 1920s Le Corbusier applied the Five points of a new architecture, of great interest to the avant- garde Belgian architects of the 1920s and 1930s. Among these, Louis-Herman De Koninck, Huib Hoste, Stynen and the Équerre group clearly showed interest in Corbusian principles. Between 1930 and 1936, Gaston Eysselinck designed several “machines for living in”, while Paul-Amaury Michel developed the Citrohan principle. It was at this time that the La Cambre Higher Institute for Decorative Arts was set up. Under the direction of Henry Van de Velde and with many Belgian Modernists among its teachers, it was a school that offered an alternative to the so-called “academic” teaching then prevailing in Belgium.

Le Corbusier had personal relationships with many of his Belgian colleagues among whom were Victor Bourgeois and Hoste, founding members of CIAM in 1928. These architects and other Belgian artists were to act as intermediaries in promoting the work of Le Corbusier in Belgium.

Thanks to the CIAM Congresses, Le Corbusier’s ideas entered the debate on urban planning and modern architecture in Belgium. In 1932 the third CIAM Congress was devoted to rational land development (“Rationale Bebauungsweisen”) and took place in Brussels in Victor Horta’s Palais des Beaux-Arts.

In the 1930s, Le Corbusier took part in the competition to build a new district of more than 100,000 inhabitants on the left bank of the Scheldt in Antwerp (the historic city having developed entirely on the right bank). Paul Otlet, the promoter of the Mundaneum proposal, encouraged Le Corbusier to participate in this Linkeroever (Left Bank) Project, suggesting a partnership with a local team including Huib Hoste and Fe Loquet. The competition was a huge success, with more than 300 entries from all over the world. The project by Le Corbusier, Hoste, Loquet and Otlet was a perfect illustration of the Ville Radieuse, but in the end no project in the competition won first prize and the civil engineer and city architect were given the task of establishing a new development plan for the Left Bank. This plan was approved in April 1934 but strongly criticised by Le Corbusier, who in 1936 was to repeat and sharpen his criticisms. These criticisms, among others, probably played an important role in the revision of the plan. Le Corbusier and Hoste proposed a project based on the official plan but completely reworked. Despite being more realistic and pragmatic, Le Corbusier’s new project was to have no influence on future urbanization of the left bank of the Scheldt.

Despite the failure of his Linkeroever project, Le Corbusier’s influence in the world of Belgian architecture and urbanism became definitively established in the years following the Second World War. His views were echoed by a generation of teachers and professors, who presented them as the foundations of the project. This modern architecture fitted well with the faith in technology characteristic of the 1950s and 1960s and illustrated by the Brussels Universal Exhibition of 1958. At this exhibition, the first to take place after the Second World War, the design of the participants’ pavilions vied with each other in ingenuity and innovation.The one designed for Philips by Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis attracted particular attention. Unfortunately, like most of the buildings, this pavilion was dismantled at the close of the exhibition.

For Pierre Puttemans, a teacher at the La Cambre Institute, the influence of Le Corbusier’s work on architectural theory and practice in Belgium from 1945 to 1970 showed itself in a number of ways:

- imitations of several key works;

- interpreting and continuing his research in architecture and urban planning, notably in the work of Willy Van der Meeren, or René Braem’s collective realizations;

- in one form or another, commercial and populist trivialization of Le Corbusier’s ideas and aesthetics;

- the search for a compromise, especially in the case of certain “early Modernists” like Victor Bourgeois, Louis Herman De Koninck or Leon Stynen;

- proclaiming and circulating functionalism and a modern aesthetic largely inspired by Le Corbusier, but also by other leading lights of contemporary architecture;

- Corbusian inspiration of Belgian Brutalism;

- a major contribution to the body of ideas in the inter-war

According to René Braem, a former trainee with Le Corbusier, and major representative of modern architecture in Belgium, Le Corbusier was the first to take the measure of the technological potential of concrete and steel. In his view, Le Corbusier was a great artist who deserves an important and permanent place in the history of architecture.